“As a city, we’re not interested in being the fastest growing city by percentage in the county. We just want a reasonable, healthy and stable growth rate for the future.”—Jason Gage, City Manager, City of Springfield.

Leadership

Facing the Growing Pains of the City of Springfield

Across our region, there’s broad agreement that growth in Springfield, Missouri is good. But how do we deal with the inevitable growing pains? Biz 417 spoke to local leaders past and present to get a clearer picture of a path forward.

by Lucie Amberg

May 2024

In January, Senator Curtis Trent prefiled Missouri Senate Bill No. 979 (SB 979) for potential adoption in the current legislative session. At first glance, the bill may sound uncontroversial. It would eliminate a requirement of annexation that effectively complicates the City of Springfield’s plans to annex certain properties within its Urban Service Area (USA).

The Urban Service Area (USA) is the area in which Springfield has an official intent to provide utilities and road maintenance, as resources allow. It’s bigger than Springfield, and it includes properties that are close to, but outside, the city limits. The City has been clear about its interest in eventually annexing some of these properties, depending on development. Many USA residents work or own businesses in Springfield and send their kids to Springfield Public Schools, and they may be able to connect to City Utilities instead of relying on private wells and septic tanks. But they can’t vote in municipal elections or serve on City boards. In some sense, bringing USA properties within the city limits feels intuitive—like the municipal equivalent of putting a ring on it.

But when news of SB 979 broke, some of Springfield’s neighbors saw it differently, and they let the public know. David Cameron, city administrator of Republic, told KY3 he was surprised that he hadn’t been contacted before the bill was prefiled. The chiefs of nearby fire protection districts—units that provide emergency services to areas outside Springfield’s city limits—expressed concern about the bill’s effect on their budgets and consequently, on their mission.

“We’ve known this could happen for years,” says Richard Stirts, chief of the Logan-Rogersville Fire Protection District (LRFPD), but one aspect of SB 979 raised particular alarm. “The new part is doing away with the ‘compact and contiguous’ piece of it, and that’s what got everyone concerned.”

He’s referring to language within current law that requires city annexations to be “compact and contiguous,” meaning that they have to connect to an existing city boundary. Jason Gage, city manager for Springfield, says that eliminating this requirement—as SB 979 would—is important for Springfield’s growth.

“We agree that keeping annexations compact and contiguous is, generally speaking, a very good planning approach,” Gage says. But within Springfield’s USA, he envisions some areas developing differently—with the earliest development happening on property that isn’t directly connected to a city boundary.

Gage thinks Hunt Branch, near southeast Springfield, will develop in this non-contiguous way. Springfield Mayor Ken McClure confirmed Hunt Branch is a focus for SB 979.

“We need Springfield to grow. It is the catalyst city. For the region as a whole, Springfield has to grow and will grow.”—David Cameron, City Administrator, City of Republic.

Purchase PhotoThis makes sense—last year, Springfield City Council approved construction of a trunk sewer line for Hunt Branch. The new line will serve locations along Highway 60 between Springfield and Rogersville. According to previous reporting, Phase 1 of construction is estimated to cost $3.9 million, and the sewer is widely considered crucial for Hunt Branch’s development. If Springfield’s going to invest in this infrastructure, it’s reasonable to want to bring that territory into the City.

But it’s currently served by the LRFPD, and Stirts says SB 979, as it was introduced, didn’t properly address the impact that Springfield annexation will have on his team’s operations. “I have no problem with them annexing,” Stirts says. “That’s part of the City’s growth. How we get there is another thing.”

Key stakeholders met on January 12 to discuss how they might get there. A couple of weeks later, SB 979 was referred to committee, and, as of press time, that’s where it remains.

What Comes Next?

This story began as a status update about SB 979, but it turned into a story about Springfield’s long-term growth, how it’s beneficial and why it’s challenging. It’s a story that has everything: crime stats, insurance rates and words like “karst” and “contiguous.” And sewers. So many sewers. It’s about the ordinary things that people rely on, like utilities and snow plowing, how these services are delivered and what happens when they come into conflict with each other. And it’s about why we need people who are willing to work it all out.

Looking Back—Way Back

Before 1976, annexing property into Springfield involved a mix of judicial, legislative and electoral processes that, frankly, sounds like a headache. State law changed in 1976, allowing for voluntary annexation. About a decade later, Springfield established the USA so that unincorporated areas would be less likely to develop without sustainable infrastructure, and in the 1990s the City began requiring USA property owners who wanted to hook up to City Utilities to sign consent-to-annexation agreements. According to numbers verified by the City in 2020 and presented at a Springfield City Council workshop last year, more than 400 consent-to-annexation agreements have been signed. Many were originally signed by developers who then sold lots to individuals, so the City estimates between 20,000 and 25,000 people are currently bound by consent-to-annexation agreements.

Even though this represents more than 6,000 acres of property that could potentially become part of Springfield, the City hasn’t been aggressive about annexing, even when voluntary consent-to-annexation agreements are in place.

This is partly because many of the properties under consent-to-annexation agreements aren’t contiguous—they’re not touching a Springfield border—so they’re not eligible for annexation, according to current law.

Words to Know

Words and phrases that are key to understanding Springfield’s growing pains.

Annexation

The process by which a governing entity, like a city, can bring new territory into its jurisdiction.

Compact and contiguous

A current requirement for annexations in Missouri. While the “compact” portion of this requirement leaves room for interpretation—it basically means annexation should reasonably appear to be a unified section—the “contiguous” portion is crystal clear. Contiguous annexation must connect to an existing city boundary.

Fire Protection District

An entity that provides specific services, which typically include responding to fires and emergencies, for properties that aren’t part of a city.

Insurance Services Office score (ISO score)

A score assigned to fire departments that can be used in the calculation of insurance rates. ISOs are assigned on a 10-point scale, with 1 being the best score.

Karst

A type of landscape that’s characterized by dissolving bedrock and features sinkholes, streams and caves. According to Living With Karst, a publication of the American Geosciences Institute, development in karst landscapes “requires special sets of rules and regulations to minimize potential problems.”

Missouri Senate Bill 979 (SB 979)

A piece of legislation, prefiled in the Missouri Senate in January 2024, that would effectively allow the City of Springfield to annex territory within its Urban Service Area without requiring the annexation to be compact and contiguous.

Prefiling a Bill

The act of formally introducing a bill for consideration at a legislative session.

Springfield’s Urban Service Area (USA)

The area in which Springfield has an official intent to provide utilities and road maintenance, as resources allow. It’s bigger than the city itself because it includes properties that are close to, but outside, current city limits.

Forward SGF, Springfield’s new comprehensive plan, identifies annexation within the USA as a priority. But so did Vision 20/20, the previous comprehensive plan. And this is kind of where we’re stuck; consider it Springfield’s “Consent-to-Annexation Era.”

And if you really want to understand the problem, you have to go back further—to the Paleozoic Era, when the karst landscape of the Ozarks was formed. Living With Karst, a publication of the American Geosciences Institute, describes karst landscapes as “underlain by limestone, dolomite, marble, gypsum and salt” and says they’re “areas of abundant resources including water supplies, limestone quarries, minerals, oil and natural gas,” many of which “make beautiful housing sites for urban development.” For 417-landers, this should sound familiar.

Here’s the challenging part: Living With Karst also says, “Urban development in these areas requires special sets of rules and regulations to minimize potential problems from present and future development.” Dr. Douglas Gouzie, professor of geology in Missouri State University’s School of Earth, Environment and Sustainability, says that if you’d like a picture of karst, just “drive down Highway 60 or I-44. Anywhere that MoDOT has cut through a hillside, you’ll see stretches of dirt and clay. You’ll see chunks of rock that are just sticking up, and that’s really what our landscape looks like.”

According to Gouzie, almost 60% of the rock in this landscape is dissolvable, a process that doesn’t require the acid rain of ’80s nightmares. “Rain is naturally a little more on the acid side because it picks up carbon dioxide that occurs in the atmosphere,” he says. “Nature would have this landscape slightly dissolving anyway—that’s why we’re the ‘Cave State.’”

And while this is beautiful, it makes infrastructure planning more complicated. Living With Karst says that poorly designed or maintained septic systems “can contribute significant pollutants to the groundwater.”

Even a maintained septic tank could cause problems, depending on the characteristics of the land around and beneath it, according to Gouzie. “This limestone landscape has a lot of passages through it,” he says. And while they’re not all massive caves, “you can move an awful lot of pollution through a two-inch firehose.”

All of which means that Springfield has a vested interest in continuing to provide sewer service within the USA, whenever possible. But given current legislative restrictions, it’s a Catch-22: If you take on the cost of building a sewer for sustainability purposes, you don’t know whether the City will fully benefit from the investment, economically.

How Statistics and Services Factor In

“Growth follows infrastructure,” says Richard Ollis, who served on Springfield City Council from 2017 to 2023. In his perspective, Springfield has been a little hesitant to act on that proposition, partly because of the cost.

“The problem with only looking at that view is you don’t, in my opinion, understand the broader scope of what annexing could do,” Ollis says. “It extends city limits, which allows more people to be eligible to vote and to serve on boards and commissions. You’ve probably heard people say they’d love to vote or serve on a commission, but they can’t because they live outside the City of Springfield.”

This discrepancy—the gap for people who are effectively Springfieldians but live outside city limits—shows up in critical statistics, too. According to data presented at a Springfield City Council workshop last year, if the entire USA became part of the City, Springfield’s population would increase by more than 65,000 people. The median household income would rise by almost 17%. “Companies look at those stats,” Ollis says, so it could make a difference in Springfield’s quest to lure chains like Cheesecake Factory and Trader Joe’s.

Incorporating the USA would also have a positive impact on Springfield’s crime rates, which means our community might not show up on as many “most dangerous cities” lists.

Of course, no one’s talking about annexing the entirety of the USA in the near future—even though this is technically what SB 979 has the potential to allow. Gage says that explosive growth isn’t the goal. “As a city, we’re not interested in being the fastest growing city by percentage in the county,” he says. “We just want a reasonable, healthy and stable growth rate for the future.” He puts this number at 0.7% to 1% per year. The cost of annexation acts as a natural restraint on the process, he says. It encourages growth that’s strategic, intentional and, ideally, paired with infrastructure investments, which is how we got to Hunt Branch and SB 979. If Springfield’s going to invest in building the sewer line for Hunt Branch, Gage says it’s best for it to become part of the City, even though he doesn’t anticipate that its earliest development will be contiguous. But Stirts says that the “compact and contiguous” restriction in current law is critical for fire protection districts like the LRFPD. Without it, a city’s development becomes unpredictable, which makes it difficult for neighboring districts to plan. “If it doesn’t have to be compact and contiguous, they can cherry-pick whatever developments they’d like,” he says. “That’s what has the fire districts concerned and worried about the wording of the bill.”

The LRFPD opened a new fire station in the Hunt Branch area in 2020, and it employs career staff. Stirts says that the buyout plan originally described in SB 979 didn’t reflect these realities because it was based on an agreement that was outlined back in 1995. But since the bill was prefiled, the LRFPD and the City of Springfield have held ongoing talks. In March, they reached a tentative understanding that would amend SB 979’s buyout plan in ways that make it easier for the LRFPD to support.

Still, while Hunt Branch may be the short-term focus of SB 979, in the long term, the bill could affect other neighborhoods. “This issue is a statewide issue for all fire districts and cities of any size wanting to grow,” Stirts says. “I cannot stress enough that the financial stability of fire protection districts depends on cooperation and legislation.” And a solution that works for the LRFPD in Hunt Branch might not work for other fire protection districts.

There’s a different piece of legislation, Missouri Senate Bill No. 1291 (SB 1291), that might address this issue on a statewide level, regardless of what happens with SB 979. If SB 1291 is enacted, fire protection districts would continue to provide services to annexed properties; in exchange for this service, the city that annexed the property would pay the fire protection district a fee that’s equivalent to the property tax revenue the district would have collected if the territory hadn’t been annexed. Like SB 979, SB 1291 is currently in committee.

The arrangement described in SB 1291 could be a reasonable compromise. But it could potentially create a wrinkle for homeowners. Fire departments are evaluated according to the Insurance Services Office (ISO) scoring system. ISOs are assigned using a 10-point scale, with 1 being the most exemplary score. These scores can be used to calculate property insurance rates. It’s reasonable to assume that homeowners will want the best insurance rates, which means they’ll want service from the fire department with the most exemplary ISO score—regardless of any agreement that exists between a city and a fire district.

Stirts says there are ways to address this question, too, but it’s all pretty complicated.

“I have no problem with them annexing. That’s part of the city’s growth. How we get there is another thing.”—Richard Stirts, Fire Chief, Logan Rogersville Fire Protection District.

Purchase Photo

“The best course of action is always communication and collaboration.”—Richard Ollis, former Springfield City Council member, local business owner.

It’s another reminder of why these problems can only be solved by people who are willing to get deep in the weeds with them. At this point, there’s no indication whether either SB 979 or SB 1291 will make it through the legislative process.

Gage says the City isn’t in a hurry. If SB 979 can be amended to reflect key compromises with Springfield’s neighbors, “there’s a good possibility that the bill will come out,” he says. “But it might be next session.” Even if the legislative process doesn’t pan out, he says there are other means by which the City might pursue annexation.

That’s happened in the past, with mixed results. An attempted annexation in 2003 narrowly failed to win voter approval. Other attempts in 2005 and 2007 were withdrawn. Some failed annexations have led to compromises with neighboring government entities, like the one in 2007, which sparked negotiations over boundaries and services between Springfield and Willard.

Springfield’s leash laws and fireworks restrictions are among the reasons frequently cited for annexation resistance, along with a desire to keep Greene County’s snow plowing services. In background conversations for this story, snow plowing services came up a lot, with Greene County consistently earning high marks for its service. While this might sound like a small decision point, it’s a quality-of-life issue every winter, and it’s the kind of thing people consider when they’re asked whether they’d rather live in the City or in the unincorporated county.

Looking Forward

Regardless of how bureaucratic these issues might sound, many of the key players believe the best path forward is a human one: They just have to keep talking about it. This is what Gage says Springfield is focused on now. “We called a timeout,” he says.

Stirts says that the initial meeting on January 12 made a difference. “Jason [Gage] and Senator Trent and the City have been fabulous to work with,” he says. “Hats off to them; they showed up to the meeting and talked through the issues.”

Ollis would love to see these conversations turn into ongoing talks about Springfield’s growth. “The best course of action is always communication and collaboration,” he says.

There are areas of mutual interest that could serve as a foundation for such talks. For example, Gage says that it’s imperative for Springfield to grow because cities can’t remain the same—if they don’t grow, they decline. And from his vantage point in Republic, Cameron agrees.

“We need Springfield to grow,” Cameron says. “It is the catalyst city. For the region as a whole, Springfield has to grow and will grow.” For him, the problem with SB 979 is that its intent isn’t clear. The bill’s immediate goal might be to incorporate the Hunt Branch area, but he’s concerned that its language could be applied more broadly in the future, especially long term, as new people step into leadership roles in Springfield. This lack of clarity creates confusion, and over time, it could erode trust.

When Cameron thinks about the future of southwest Missouri, he draws from his past experience as a city administrator in northwest Arkansas, which is widely known for its approach to regional development. There, he says, collaboration not only produced mutually beneficial growth; it also increased the region’s persuasive power when it was advocating for legislative outcomes.

Cameron says the Alliance for Healthcare Education, the new partnership between CoxHealth, Missouri State University, Ozarks Technical Community College and Springfield Public Schools, offers a good model for how this approach can work here.

The Alliance unites different entities around the shared goal of training health care professionals. “That was an opportunity because one organization can’t do it all on their own,” Cameron says. “That’s what regionalism is to me. It’s not just about how cities grow, but about what support services you need in those cities to continue to grow.”

If Springfield and its neighbors worked in a similar fashion, Cameron acknowledges that there’d be some negotiating and bartering, but every conversation wouldn’t be conducted from a defensive crouch.

He sees areas—like evaluating current boundary agreements between cities—that offer chances for win-win solutions. “The regional culture is starting to evolve, and [SB 979] is revealing one of the pain points,” Cameron says. “We should be grateful when these things get exposed because these are places where we can adjust and adapt, moving forward with a whole new culture and mindset… Southwest Missouri has so much to offer and so much potential, but we have to work collectively.”

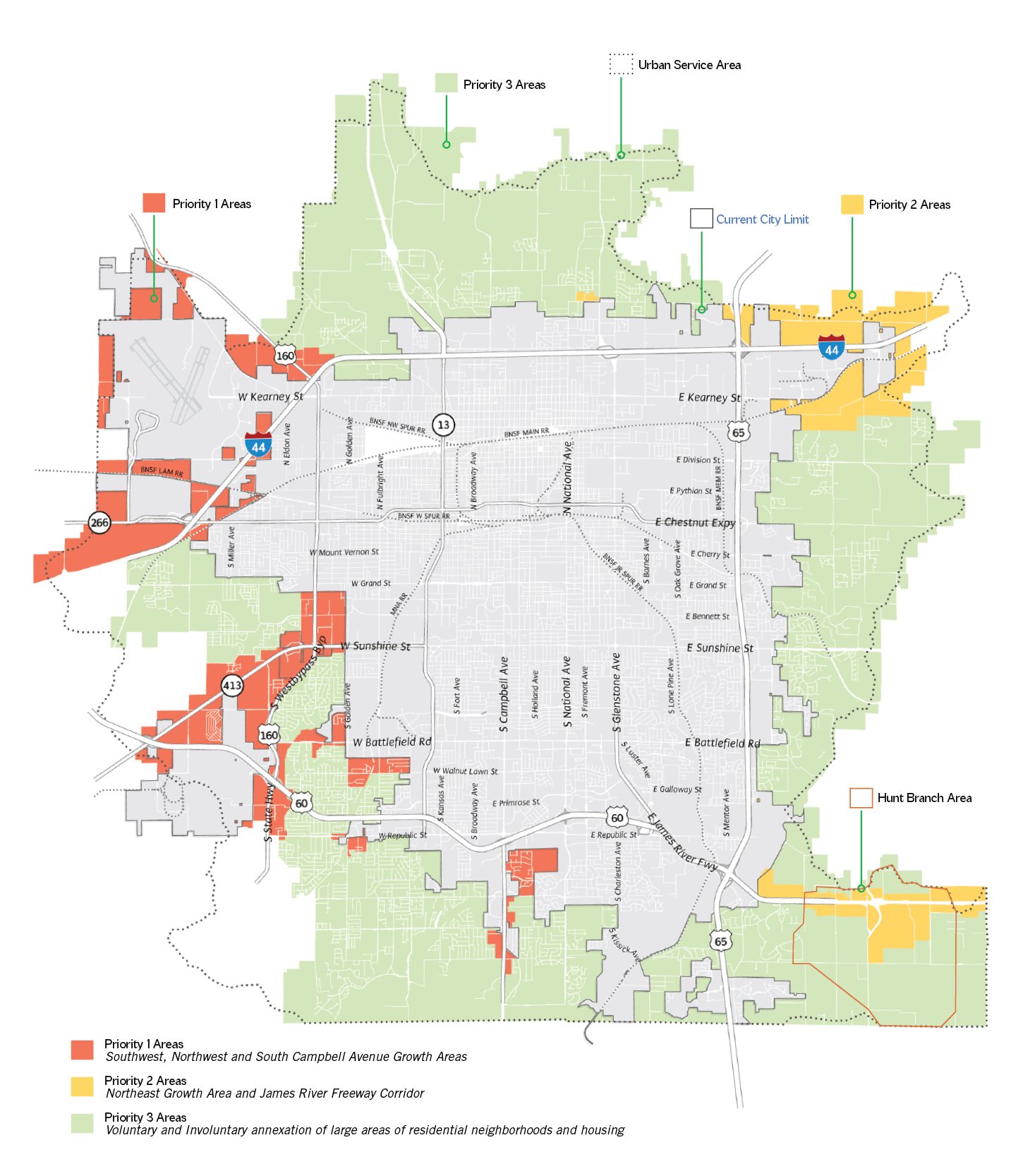

Springfield, Missouri's Roadmap

Take a look at the annexation plan below. Gray areas note the current city limit boundaries. The colored areas designate the priority levels on the horizon for annexation. Map is courtesy of The City of Springfield and can be found on ForwardSGF’s website.

In November 2022, the City of Springfield adopted the Forward SGF Comprehensive Plan. It provides a vision for the Springfield of 2040, along with specific ideas about how to get there. Growth by annexation is among Forward SGF’s top 10 initiatives. The plan envisions annexation as something that will happen within Springfield’s Urban Service Area (USA) and identifies parts of the USA as priorities for annexation. It recommends that the City consider an area’s annexation potential as it evaluates infrastructure improvements. This lines up with what Springfield City Manager Jason Gage told us about the intent of Missouri Senate Bill 979—that it was sparked by Springfield’s plan to build a sewer line in Hunt Branch, which is currently unincorporated territory in Greene County. It feels like an intuitive approach; assessing annexation potential when you’re committing to infrastructure spending seems like reasonable fiscal policy. Forward SGF echoes another idea that was expressed by sources we spoke to for this story—the need for regional cooperation and communication. According to the Forward SGF website: “It is critical the City works closely with surrounding municipal and county governments, utility providers, the regional planning agencies, business and environmental groups and other stakeholders. The City should facilitate conversations on topics that promote sustainable growth, a resilient economy and stewardship of the natural and built environment in the greater Ozarks region.”