Strategy

Altered State: The Business of Pot in Missouri

High expectations or reefer madness? We tackled four burning questions raised by the medical marijuana law Missouri overwhelmingly approved and how this new industry could impact health care, the workplace and our economy in southwest Missouri.

By Adrienne Donica | Art Directed by Sarah Patton

Sep 2019

On November 6, 2018, Missourians made a choice about the future of medical marijuana in the Show-Me State. Well, actually they made three.

The ballot asked voters in three separate questions if they wanted to legalize medical marijuana. Having two constitutional amendments and a proposition, all regarding this issue, on a single ballot was unprecedented among the 31 states where Mary Jane was already considered medicine. Passing with nearly 66% of the vote, Amendment 2—known as Article XIV—was the one that stuck.

Since then, the Department of Health and Senior Services has created the industry’s regulatory division, led by Marshfield native and former State Rep. Lyndall Fraker. Fraker and his team are responsible for registering patients and evaluating and certifying six commercial applicant types: cultivation, manufacturing, testing and dispensing facilities; transportation companies; and seed-to-sale tracking systems businesses must use to detect and discourage the diversion of legally grown pot into the illegal market.

Now, what started as three questions has led to a whole lot more: Who in southwest Missouri will be involved in the medical marijuana industry? How many patients want to use this new treatment option, and which doctors are willing to certify them? Now that weed is coming, is there an economic windfall in Missouri’s future? And just what ramifications will the industry have for businesspeople not involved in cannabis?

It’s easier to pin down some of these answers than others. To put it bluntly, there’s still a whole lot about the future of the state’s medical marijuana program that remains hazy.

SO YOU WANT TO START A POT BUSINESS? GET IN LINE.

There’s no doubt Missouri is excited about medical marijuana. Campaign organizers tout that the amendment garnered the most votes of any issue or candidate on the November ballot. And nearly everyone is surprised at how many businesses pre-filed application fees, which the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services (DHSS) started accepting for cultivation, manufacturing and dispensary facilities on January 7. Three days later, the state reported receiving more than $2 million from 250-plus would-be applicants. By August 1, two days before the official application period opened, the department collected $4,418,000 in early fees from 621 applications.

“When you look at the pre-applications that have been filed with the department, it’s really staggering,” says Jack Cardetti, former consultant and spokesperson for New Approach Missouri, the group that backed the ballot initiative. Cardetti now serves as spokesperson for the Missouri Medical Cannabis Trade Association, more commonly known as MoCannTrade. The campaign thought the department would collect $1.5 million to $2 million in pre-filed fees, slightly higher than the $1,134,000 that the state auditor’s office projected in the amendment’s fiscal evaluation. Both estimates were extremely low.

Applicants who chose to pre-file weren’t given any special advantage, but some saw it as a good faith investment in the state’s newest industry. Those fees meant DHSS could support the medical marijuana division without diverting funds. Of the nearly $4 million DHSS had collected as of July 2, $636,000 came from 25 counties in southwest Missouri. Those fees were generated by applications for 27 cultivation facilities, 10 manufacturing operations and 51 dispensaries, some of which were filed by the same company representative. (Under Article XIV, one business entity can operate five dispensaries, three manufacturing facilities and three grow operations. Testing centers must operate independently, and DHSS did not accept pre-filed fees from these applicants.) The application fee is $10,000 for cultivation licenses and $6,000 each for manufacturing and dispensary licenses.

Not every hopeful southwest Missouri marijuana entrepreneur chose to submit fees early, but some did seek support from the City of Springfield, which created special medical marijuana zoning certificates. These certificates could help area business owners edge out the competition by proving they have secured a place of business that has been inspected by the city. Springfield received 19 medical marijuana zoning certificate applications from 13 people between June 4 and July 5, when Biz 417 received the records. Only two certificates matched applicants from the state’s records. At press time, the City had received 86 applications, approved 60 and denied one.

Because the state will only grant licenses for 60 cultivation operations, 86 manufacturing facilities, 192 dispensaries and 10 testing centers, the competition is blazing hot. “It’s so much more competitive than I could have ever expected,” says Canna Bliss owner Jamie Tillman, who hopes to dispense medical marijuana at three Springfield locations. “I didn’t realize how many out-of-state huge dispensary companies… are going to try to get into Missouri. It’s just a lot more money involved than what most people realize and a much bigger and a much more aggressive process.” The law mandates the majority owner of any cannabis company be a Missouri resident, but out-of-state investors can be involved and often offer vital institutional knowledge. “Easily, to put in these applications, you are looking to invest up to $100,000,” Tillman says.

In addition to the application fees and business expenses, companies granted licenses must also pay annual operating fees—$25,000 for cultivators and $10,000 for manufacturers and dispensaries—and facility agent fees for any employee or contractor. The agent certification process also requires a federal background check; to register one employee, it will cost $116.75. For testing centers, transportation companies and seed-to-sale systems, the application fee is $5,000 as is the annual operating fee. What’s more, the state asks applicants to demonstrate they have between $150,000 and $300,000 in liquid capital. That’s a lot of money for business owners who generally can’t get bank loans.

Instead of loans, these entrepreneurs have to find private equity investors or rely on their own assets. Even more of a puzzle is operating a business without a bank account. Imagine not being able to process credit or debit card payments from customers and having to pay all your expenses—including payroll and taxes—in cash. That’s the reality for most medical marijuana businesses in the country.

“The primary issue for the banking industry is, from a federal law standpoint, marijuana is still an illegal drug under the Controlled Substances Act,” Shaun Burke says. “All banks are subject to federal law. So if we do anything to bank… a marijuana-related business, we are violating federal law.” Burke is president and CEO of Guaranty Bank and served as the Missouri Bankers Association chair in 2018. He says this inconsistency between federal and state laws is one of the top issues for MBA and its national counterpart, the American Bankers Association. If marijuana becomes legal, the banking headaches would go away, but for now, institutions are left without much direction.

Back in 2013, U.S. Deputy Attorney General James Cole issued a memo that identified clear priorities for the Justice Department when it came to cannabis. Banking was mostly left alone, meaning financial institutions had more leeway to dictate policies for working with marijuana-related businesses (MRBs). But in January 2018, then-U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions rescinded the Cole memo. Three bipartisan bills—including one to deschedule cannabis—could provide banks some respite, but none have made it to a full-chamber vote.

According to a report from FinCEN, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, 493 banks and 140 credit unions nationwide were providing services to MRBs as of March 2019. In Missouri, only one bank has publicly announced it will serve this clientele. In May, Triad Bank CEO and President Jim Regna told Marijuana Business Daily his organization, which is based in the St. Louis suburb of Frontenac, would offer deposit services. Regna declined to be interviewed for this article because he had been contacted by the federal government and didn’t want to draw more attention to the bank.

“The primary issue for the banking industry is, from a federal law standpoint, marijuana is still an illegal drug under the Controlled Substances Act.”— Shaun Burke, President & CEO of Guaranty Bank

This cash-based industry also presents a challenge for tax collectors. In addition to paying business taxes at the federal, state and local levels, MRBs have to pay sales taxes at the state and local levels. Article XIV also created a 4% sales tax to support a new fund, the Missouri Veterans’ Health and Care Fund, but stipulates the sale of pot cannot be taxed any other way. The state auditor projected the amendment would generate $18 million in annual taxes and fees and provide $6 million in tax revenue for local governments, but a report by several University of Missouri economists determined the state could collect $1.2 million and $1.6 million in taxes in 2020. The tax estimates are low because the patient estimates are low. By 2022, tax figures could reach $2.9 million or $3.4 million, according to the report.

Even the lower estimates, if paid in cash, would be taxing for companies and Missouri’s Department of Revenue. In early July, a department spokesperson told Biz 417: “The Department of Revenue is currently evaluating procedures to accept tax revenue from medical marijuana businesses. The department will create a reporting form and will make necessary changes to our processing systems to collect the tax.”

DOR has tax assistance offices around the state, including one in Springfield and another in Joplin. Business representatives can make payments at any location, but cash is only accepted at the Jefferson City office currently. There’s still plenty of time for DOR to sort this out. DHSS must award facility licenses by December 31 for applicants who applied on August 3, the first day the application portal was open, and even if they beat that deadline, it’s likely marijuana companies won’t be open until next spring.

TIMELINE FOR CREATING MISSOURI'S MEDICAL MARIJUANA PROGRAM

Amendement 2 passes.

Medical marijuana is legal.

Some applicants begin to pay license fees.

Rules and application information released 11 days early.

Six days early, patients and caregivers begin to register.

Businesses apply for licenses. Transportation and seed-to-sale certificates will be accepted indefinitely.

Earliest deadline for DHSS to award licenses.

Earliest time dispensaries could be operational.

HOW MANY PATIENTS ARE EXPECTED TO LIGHT UP?

As exciting as the response from the business community has been, Article XIV is first and foremost a health care law. “Our primary concern was and remains the welfare of patients,” says long-time marijuana reform advocate Dan Viets, who serves as board chair of the Missouri Cannabis Industry Association and was president of New Approach Missouri. “The industry exists to serve patients.”

Like most other states that have legalized medical marijuana, Missouri has qualifying medical conditions residents must have in order to register for a patient ID card. Article XIV lists 22 diagnoses, including cancer, epilepsy, HIV/AIDS, PTSD and glaucoma. But the article also gives doctors leeway to certify patients with persistent pain, terminal illness or a “chronic, debilitating or other medical condition.”

To be approved for an annual ID card, a patient must submit an application to the state and a corresponding $25 fee. They also must have a licensed Missouri medical doctor or doctor of osteopathy in good standing complete a certification form stating the patient has one or more of the qualifying conditions. The form requires doctors to acknowledge they have reviewed the patient’s medical history and discussed the risks of medical marijuana with the patient. Unlike a traditional prescription though, doctors are only required to specify dosing amounts if qualifying patients need more than 4 ounces of dried, unprocessed cannabis or its equivalent in a 30-day period. (The MU report found that patients in Massachusetts and Arizona consumed on average a little more than 10 ounces in 2018.)

So how many people will get certified? We won’t know until the program is more established, but 548 people applied for an ID card on the day DHSS opened the registration portal. At press time, 6,050 patients and caregivers had been approved. Meanwhile, various stakeholders have been making estimates of anywhere from tens of thousands to nearly a couple hundred thousand people statewide.

DHSS is expecting 2% to 3% of Missouri’s 6.1 million people to apply for cards within the first three years. When writing the amendment, New Approach Missouri was slightly more conservative and projected 1.9% to 2.7% of the population would be certified. This was based on data from Colorado and Oregon, which have similar qualifying conditions to Missouri. “We… also adjusted it upwards a little bit because of the fact that we have a higher rate of chronic disease in almost every category than the states of Oregon and Colorado,” New Approach Campaign Manager John Payne says. Using these two projections, as many as 183,800 Missourians—roughly 20,100 to 31,700 of whom might live in southwest Missouri—could seek relief from pot.

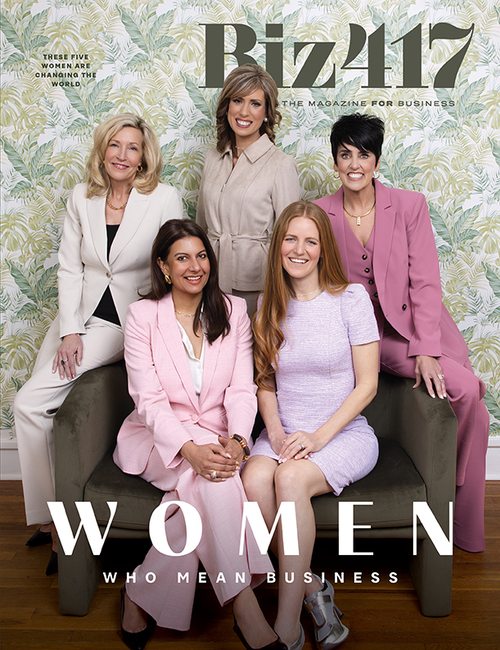

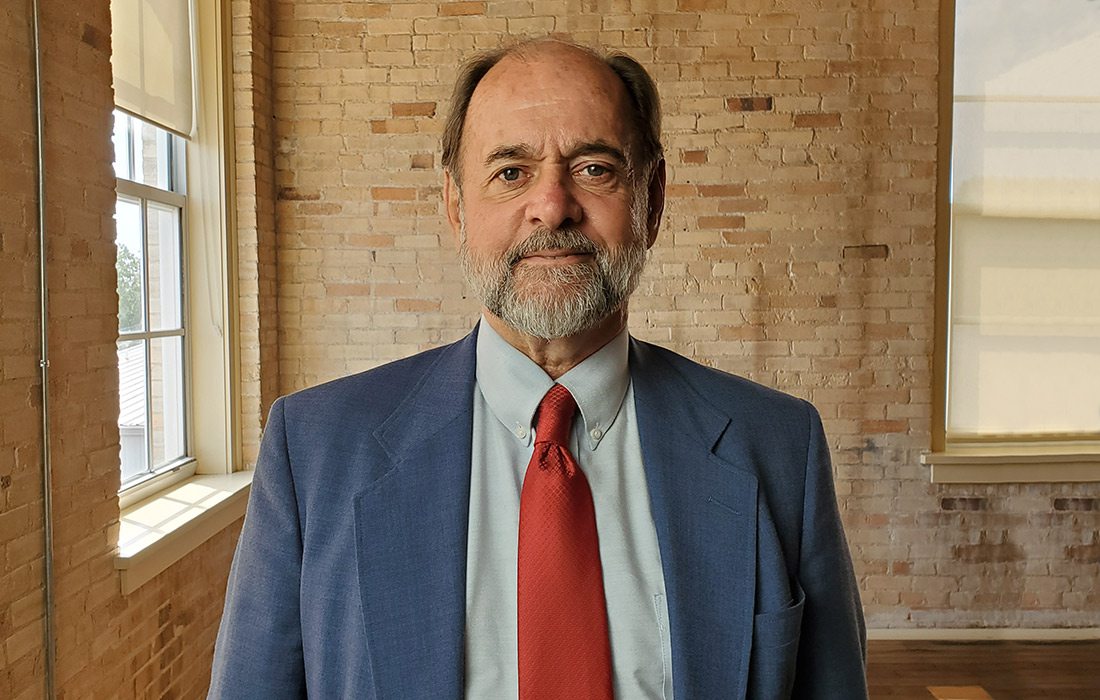

Photo courtesy Joe Haslag Joe Haslag, University of Missouri Economics Professor

Another set of projections comes courtesy of MU’s Economic and Policy Analysis Research Center, led by Springfield native Joe Haslag, who is an economics professor and the Kenneth Lay Chair. DHSS commissioned Haslag and two of his colleagues to study the potential market in Missouri. They released their findings this spring. “I was really hopeful walking into this,” Haslag says. “I thought, ‘There’s some states that have long histories in this. I’ll get some great data for 10 or 15 years…’ But the data just don’t exist.” Using the number of patients enrolled in 19 states’ medical marijuana programs from September 2015, the best available data, Haslag and his colleagues found that, on average, 0.7% of a state’s population are qualified patients. When accounting for the fact that many of these programs have already existed for several years, the economists predict just 0.3% of Missourians, or 19,000 people, will become qualified patients in 2020. By 2022, they expect the patient population to grow to 26,100.

We talked with Haslag this summer, and he offered a more hopeful outlook. “Missouri is really trying to model itself [on Arizona],” he says. “If you used Arizona’s fraction of population and how long it took them to get there, we could be as big as 60,000 within the first year.” That equates to about 1% of Missouri’s population, or 10,300 patients across southwest Missouri.

These numbers—anywhere from 26,100, the official MU report projection, to DHSS’s 183,800 or so—should be taken with a grain of salt. That’s because anyone who offers an estimate relies, at least in part, on the number of patients who use weed in the 32 other states and District of Columbia, where medical marijuana is legal. None of the existing medical marijuana programs are identical, and data reporting methods are just as varied. Most importantly, those places aren’t Missouri. So, right now everyone is just making their best guess, and it’s too soon to say who will be right.

One factor that will likely impact how many Missourians start using marijuana as medicine is the number of certifying doctors. Many large health systems that rely on federal funding are hesitant to allow physicians to certify patients while marijuana is still a Schedule I drug, and many doctors don’t know much about using marijuana as a treatment option.

Two days before the state began accepting patient applications, Mercy announced in a statement that its physicians would not be certifying patients because “there is insufficient medical and scientific research on the benefits and risks of cannabis products as part of medical treatment.” CoxHealth and Joplin’s Freeman Health System followed suit the next day. “Because we must certify every year that we are in compliance with all federal laws, or risk losing the ability to provide care for Medicare and Medicaid patients, we cannot act in a manner that is in any way inconsistent with federal law,” a statement from CoxHealth said, adding that any physician with privileges to see patients at CoxHealth is also barred from certifying patients at the health system’s facilities.

“Article XIV outlines 22 specific diagnoses...but also gives doctors plenty of leeway to certify patients who have persistent pain, any terminal illness or a 'chronic, debilitating or other medical condition.'”

Burrell Behavioral Health, which provides mental health services for 25 counties in Missouri and Arkansas (where medical marijuana is also legal), doesn’t currently have a formal policy for patient certification. “Burrell remains committed to evidence-based practices of care and will continue to research this subject as it concerns our clients,” a Burrell spokesperson says. At press time, Citizens Memorial Hospital in Bolivar and Ozarks Medical Center in West Plains were still working on their policies. Ozarks Community Hospital did not return requests for comment. But southwest Missourians won’t have to travel outside the region if they're looking for medical marijuana. Several local private practitioners are signing certification forms and say they mostly made their decisions to do so based on patient need as opposed to the business opportunity the certification process offers.

“The phones are ringing off the hook,” Dr. Lisa Roark says. “It’s unreal.” She opened Roark Family Health in 2015 and served on New Approach’s advisory board. “Especially after realizing that the major health systems were not going to be allowing their doctors to do certifications, I realized at that point… independent docs have to be a part of this or else patients aren’t going to be able to get certification,” says Roark, who is also hoping to open a dispensary. She submitted the $6,000 application fee to the state back in January. Under Article XIV, doctors can own, operate, invest in or contract with medical marijuana businesses.

One reason Roark's Cassville clinic has been so busy is because she and her fellow staff physician will certify patients in-person or via video visit. The service is free for members, and $100 for nonmembers.

“There are a lot of clinics that are charging $250 to $300 and requiring drug screens and all these hoops to be jumped through, and to me, that’s not the intent of the law,” Roark says. “So my thought is if I offer telehealth visits, it will help drive down that ridiculously high cost that is being charged at several clinics.” Because of the demand, Roark is in the process of hiring an additional physician and physically expanding the clinic.

HOW CANNABIS BUSINESSES GET CERTIFIED

Secure investment, create a business plan and lease or buy property that complies with local regulations. Springfield applicants can choose to complete and pay for a zoning certificate from the City of Springfield, a process that requires a city inspection.

Third-party evaluators blindly review applicants for cultivation, manufacturing, dispensary and testing center certificates before DHSS finalizes the scores and awards licenses.

Facilities must request a state commencement inspection within a month prior to opening before they can legally operate.

Businesses must submit renewal applications five to eight months before their licenses expire.

Unlike Roark Family Health, two Springfield-based independent clinics certifying patients, Elite Pain Management and Command Family Medicine, will require drug tests. Evaluations at Elite cost $200; meanwhile, Dr. Luke Van Kirk, who owns Command Family Medicine, will only certify members of his practice, which has an annual fee of $1,020, or $720 for 18- to 26-year-olds. At press time, physicians at Roark Family Health and Elite had signed about 970 certification forms. (Although retail sales won’t begin until 2020, DHSS is allowing patients to begin home-cultivation once they have successfully registered for an ID card and cultivation permit.)

There are also at least four so-called “cannabis clinics” setting up shop in the area. These offices connect qualifying patients to doctors who will certify them. Cannabis Doctors US has an office in Monett, and Missouri Marijuana Card owns Springfield Marijuana Doctor on East Sunshine Street. Two other businesses, The Green Clinics and Green Health Docs, are planning to open clinics in Springfield. All four companies operate multiple locations across the state, and in the case of all but The Green Clinics, across the country.

These homegrown practices and budding cannabis clinics will have their work cut out for them if 20,000 or so southwest Missourians end up seeking medical marijuana IDs cards. “I wish there were more doctors available because the more doctors that are available at a reasonable cost, the more patients who can be helped,” Roark says.

WHAT DOES THIS NEW INDUSTRY MEAN FOR SOUTHWEST MISSOURI JOBS, REVENUE AND PATIENTS?

You don’t have to be an economist to understand the importance of patient certification. The success of the industry is dependent on medical sales, meaning registered patients are the only ones driving demand. The more patients who are out there buying products, the more taxes will be generated. More patients also means increased demand, which can lead to an increase in jobs at licensed medical marijuana facilities.

“First and foremost, Missouri’s medical marijuana program is going to be a godsend for Missouri patients, and that’s the most impact that we’re going to see,” MoCannTrade’s Cardetti says. “But the secondary impact is really going to be on Missouri’s economy.”

In a slow-growing state like Missouri, any economic growth helps. In 2017, the state’s GDP was $263.1 billion, according to the Missouri Economic Research and Information Center, a division of the state’s Department of Economic Development. With 60,000 qualified patients, Missouri’s medical marijuana industry would likely be worth around $100 million. “A $100 million industry is nothing to laugh at,” Haslag says. “But this is not going to change Missouri’s growth outlook from being a relatively slow-growth state to now a relatively fast-growth state. It’s almost a trickle out of a $300 billion economy.” Plus, the market will experience substitution as jobs and investment move from other industries to medical marijuana, he adds. Haslag’s projection is similar to one found in the fiscal evaluation of the amendment prepared by the state auditor that places the value of the medical marijuana industry at roughly $155.7 million by 2023. The DED had not done any economic analysis of the new industry as of early July, according to a department spokesperson.

Nationally, the combined medical and recreational marijuana market continues to grow at an exponential rate, adding tens of thousands of jobs and contributing billions to the economy each year. In 2018, marijuana was a $10.4 billion industry that supported a quarter-million industry-specific jobs, according to New Frontier Data. By 2021, The Arcview Group anticipates the medical market will reach $7.7 billion, and the industry as a whole will provide more than 291,500 full-time equivalent positions. The impact on the national economy could be as much as $39.6 billion that year. More than 60% of that will likely be created by six states where recreational pot is also legal; Arcview estimates Missouri’s contribution will be $28 million.

Only time will tell if any of these projections are true, but Missouri is guaranteed to gain new companies when DHSS awards nearly 350 licenses later this year. Furthermore, parts of the law could provide an advantage to applicants hoping to operate in southwest Missouri.

“It’s reasonable to expect that the medical marijuana industry could generate between 5,000 and 15,000 jobs.”— Lyndall Fraker

Though DHSS is choosing who gets licenses blindly, Article XIV stipulates each congressional district must have at least 24 dispensaries. This ensures patients have reasonable access but also helps distribute the industry’s economic impact somewhat. The law requires DHSS to evaluate applicants based on security, business planning, applicable experience, “the potential for positive economic impact in the site community” and “maintaining competitiveness” in the marketplace. As such, the department added scoring bonuses to applicants with anticipated facility locations in economically distressed areas, defined as zip codes with employment rates below 90%. The bonus is higher if a facility plans to be located in an area where employment is below 85%. Dispensaries can also receive a bonus if they are more than 25 miles away from any other applicant or existing facility.

Based on census data, southwest Missouri is home to 39 of the 155 economically distressed zip codes, or 25.2% of the total number. And 21.8% of the most vulnerable districts, of which there are 55, are in southwest Missouri. As you might imagine, these areas are in rural parts of the region. Only six of the 105 applications that pre-filed fees or submitted a City of Springfield zoning certificate by early July had anticipated setting up facility locations within an economically distressed district. These include three dispensaries, two cultivators and one manufacturer in Aurora, Buffalo and Cassville, which have employment rates between 88.5% and 89.1%. There’s no guarantee these six operations will be granted licenses, but if they are, they could bring much-needed jobs to the area.

Fraker says that statewide, it’s reasonable to expect that the medical marijuana industry could generate between 5,000 and 15,000 jobs. Even in the region’s larger metropolitan areas, these jobs will be welcome, especially because some come with high wages. Master growers and extractors can earn as much as six figures, which is well above the $34,775 median annual income in the Springfield area. Budtenders and trimmers, who work in cultivation facilities, earn closer to $30,000. Industry experts anticipate cultivators will offer the most jobs from a single license, while dispensaries will produce the greatest collective number of jobs and the most revenue for an area.

Jamie Tillman currently has six mostly full-time employees at her CBD stores. She already anticipates hiring an additional 35 people or so if she is granted the three licenses she’s hoping to secure. Another potential medical marijuana entrepreneur, former NFL player Grant Wistrom, expects to hire 50 to 100 people if his vertically integrated company, Revival 98, materializes. Wistrom teamed up with a Colorado-based cultivation expert who plans to relocate to Missouri if Revival 98's applications are approved.

“I feel very strongly about this community and being a part of it and helping out any way that I can,” Wistrom says. “We could have found cheaper pieces outside of city limits… but we wanted to impact the city of Springfield in a positive way through revenue generated but also jobs created.” Wistrom is still putting his team together but is seeking qualified pharmacists to guide patients to the appropriate strain for their symptoms. “Each strain can impact people differently so it’s not just a one-sizes-fits-all sort of thing,” Wistrom says. “We have to be intelligent about this and make sure we’re protecting patients and providing a secure, safe environment for that to happen in.”

Regardless of how the medical marijuana industry performs in Missouri, cannabusinesses won’t be operating in a vacuum. Security firms, lawyers, accountants, marketing agencies and transportation companies are just some of the ancillary services the medical marijuana industry will rely on in the coming years. That means more opportunity for existing southwest Missouri businesses.

CAN YOU BE FIRED FOR USING MEDICAL MARIJUANA?

So, let’s say you’re in a position to gain a client working in the medical marijuana industry. It’s just like any other client relationship, right? Not exactly. By federal law, financial institutions have to file a report with FinCEN on transactions that might signal criminal activity, so if your banker notices suspicious transactions, he or she has to decide whether to do anything about it.

Even if you don’t work with MRBs, you aren’t off the hook. A Springfield manufacturer conducted a blanket drug test of its second shift this past fall. Of the 100 people tested, 20 had positive results for marijuana and were fired per company policy. “When unemployment is basically 2.5% in the city… it’s tough to replace that many people without a loss of productivity,” says Sally Payne, the assistant director of Springfield’s Workforce Development Department (no relation to John Payne). The manufacturer in question shared this experience at one of the department’s quarterly roundtables prior to legalization in November. After that, “we knew we immediately had to get to work and start the education,” Payne says. The department has now held two well-attended events about marijuana in the workplace.

Article XIV says employers can prohibit their employees from being under the influence of marijuana while at work and can discipline or even terminate anyone who does so or attempts to do so. What it does not address is whether carrying a patient ID card is covered under the ADA or other Missouri disability rights laws. It also doesn’t define what being under the influence of marijuana is.

“Currently with marijuana, there’s no way to tell level of impairment,” says Angela Garrison, Tomo Drug Testing’s vice president of operations. “There’s two reasons for that: One, there’s no technology that will tell us, and two, there’s no standard levels of impairment like there are with alcohol.” Depending on the type of drug test used, THC can be detected within a few hours after use but remains detectable anywhere from a few days to a week or even a couple of months later.

To complicate matters even further, medical review officers, who determine if a positive drug screen is due to a medical reason, do not consider a medical marijuana card a valid reason to overturn the positive result. In most instances, the report Tomo’s clients see will include the positive result with a note mentioning whether the person in the report is a qualified patient. “Depending on what the employer’s policy says, that is a huge distinction,” Garrison says. “Technically if [zero-tolerance] is your policy, you have to terminate that employee.”

For some, it’s tempting to have a zero-tolerance policy for marijuana use and classify all positions as safety-sensitive, or roles that present clear safety concerns for employees or others. “I think that’s likely to be challenged, but that’s just speculation on my part,” Springfield’s HR Director Darla Morrison says. “I think it’s hard to say all of your positions are safety-sensitive positions. I think that usually diminishes your argument for the positions that have a strong safety-sensitive orientation.”

We reached out to 25 of the area’s largest employers to ask about their policies and heard back from 15 companies. Most companies were still in the process of determining and finalizing their policies, but three—the City of Springfield, Phoenix Home Care Inc. and Paul Mueller Co.—indicated they are willing to work with employees to determine if an accommodation can be made. All prohibit employees from being under the influence while at work, and by federal law, all DOT employees are prohibited from using medical marijuana at any time. Likewise, employees of Mercy, CoxHealth and Oxford HealthCare (an entity of CoxHealth) are not allowed to work while impaired. Mercy did not clarify if staff could use medical marijuana when they are not working or if it would accommodate requests. Cox said, “We will work with employees, in accordance with our policies and applicable laws, to arrive at safe and appropriate resolutions for CoxHealth and individual employees” who have tested positive for prescribed or certified substances. O’Reilly Auto Parts prohibits medical marijuana use, Missouri State University is still deciding if or how it will update its policy (currently controlled substance use is banned), and Springfield Public Schools said it does not have a policy nor is it working on one. A spokesperson for Missouri’s Office of Administration was not sure if a policy was being worked on and said that policy would not necessarily apply to all departments within the state government. JPMorgan Chase declined to comment.

“There’s also the big question of whether or not medical marijuana is something that needs to be accommodated in the workplace in connection with a disability,” Neale & Newman LLP Associate Nate Dunville says. Many of the qualifying conditions under Article XIV can also be protected by ADA. Some interpret that to mean employers are required to make reasonable accommodations for any known employees using medical marijuana when not at work. (No law requires employees to disclose marijuana use.) However, ADA doesn’t cover those who use illegal drugs, and marijuana is still illegal at the federal level. Because of this, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in 2012 that ADA does not require a medical marijuana accommodation, but other courts have disagreed.

Missouri courts will likely rule on this issue to offer guidance, but in the meantime, Sen. David Sater, R-Cassville, is attempting to do just that with Senate Bill 227. The bill, introduced in January, would allow employers to refuse to accommodate medical marijuana use and to fire employees who test positive for THC, regardless of when they used marijuana. Sater did not return requests for comment, but the former pharmacy owner previously spoke with the Columbia Missourian about the bill. “I don’t want someone who shows positive for marijuana involved in my business,” Sater told the newspaper. “I wouldn’t feel comfortable knowing that I had someone who was using, even for medicinal use.” In February, SB 227 was voted out of the Small Business and Industry Committee, but no further action was taken before session ended in May.

MISSOURI'S MEDICAL MARIJUANA INDUSTRY BY THE NUMBERS

Number of marijuana business applications from 417-land that pre-filed fees or submitted a City of Springfield zoning certificate as of early July.

The length of time facility licenses are valid for.

Pre-filed license fees collected as of July 2

Minimum distance Springfield marijuana businesses must be from schools, daycares and churches

Amount of flowering canopy space cultivators can grow indoors. Outside, cultivators can grow up to 2,800 plants.

The best thing companies can do right now is review and update their drug use and testing policies as well as all job descriptions to determine which, if any, are safety-sensitive. Additionally, they should train supervisors on signs of impairment and share finalized policies with all employees. “Now is the time to be looking at these things,” Garrison says. “You don’t want to be caught flat-footed on this and have an employee that comes to you with a medical marijuana certification and then you don’t know what to do.”

Dunville also recommends continuing to monitor the ever-changing laws because what the future holds is anyone’s best guess. “We just don’t know right now,” he says. “We can look to other states and see how their state laws are being interpreted by the courts. We can look at federal cases to see how the interaction with federal courts is going, but until cases start getting litigated dealing with the Missouri amendment, we just won’t know how this Missouri law is going to be interpreted and enforced.”

What Dunville says could just as easily apply to the future of the entire industry in Missouri. Legalizing medical marijuana will bring new businesses, jobs and tax revenues to the state and to southwest Missouri. Patients will have access to a new treatment option, and doctors will be there to certify them. But for every known quantity, there are many more unknowns. We’ll all just have to wait for the smoke to clear.