When I think about downtown Springfield, I think about happy memories, like the night that Billy, John and Karen McQueary first welcomed guests to Vantage Rooftop Lounge and Conservatory, revealing a spectacular new way to look at our city. I think of all the times I’ve picked up pastas and cakes from Jenny Russo at St. Michael’s. I think about fireworks at Springfield Cardinals games and sweet faces peering at macarons in the cases of European Café. I remember the evening my family joined hundreds of 417-landers in Park Central Square to celebrate as a spruce from our yard became the City of Springfield’s Christmas tree. And the time we grabbed supper at Prairie Pie before walking through a magical twilight to catch a movie at Moxie Cinema. All of these warm feelings—I associate them with downtown.

When I’m downtown—say, walking from my car to meet a friend for coffee—I’m often approached by someone asking for money. I have compassion for anyone whose circumstances are such that they feel compelled to ask a passerby for help, and intellectually, I know that person probably means me no harm. But by this point in my life, I’ve experienced so many sticky situations that when any stranger, especially a male stranger, approaches me on the street, my whole body goes into high-alert mode. And unfortunately, that’s another feeling I associate with downtown.

In our interview with Springfield Chief of Police Paul Williams, we ask, “Is downtown safe?” Williams says that it is and supplies statistics to back up his statement. Regardless, people tell us that they sometimes feel unsafe downtown. This may be because we tend to mix our concerns about crime with our concerns about homelessness, even though they’re separate issues. In fact, according to research, including data from the peer-reviewed journal The Lancet, a person who’s homeless is more likely to be a victim of crime than someone who has housing. This makes sense—someone who’s living without the benefit of housing is in a uniquely vulnerable position. Still, in that moment when a stranger approaches me on an empty sidewalk, I feel vulnerable, and it affects how I feel about being downtown.

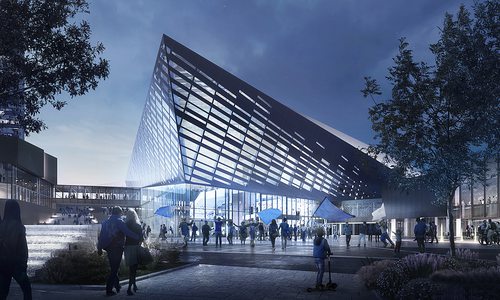

So how do you contend with a feeling? One theory, articulated by Jane Jacobs in her 1961 book The Death and Life of Great American Cities, holds that downtown neighborhoods feel safer when there are more people around. Jacobs believed that empty spaces can feel lonely, abandoned—a little unsafe. But the same spaces can feel vibrant and secure when the sidewalks are busy and the vibe is bustling.

Echoing this idea, many of the sources we spoke to for this story mentioned the importance of getting more people downtown. The big question is: What might make that happen? John McQueary hopes to see more creative professionals opening offices downtown. Jenny Russo would like more retail in the district. Tim O’Reilly is optimistic about the ability of upscale destinations to lure people downtown. Brad Erwin wants more people to work—and live—in the neighborhood. “The more activity you have, the safer it becomes and the more people feel comfortable to come downtown,” he says. Two business owners, Benjamin Sapp and David Bauer, bring up a practical consideration that may be keeping workers away: parking. Bauer also proposes a surprising idea for where the City of Springfield might designate additional parking spaces.

No matter what downtown’s future looks like, it will have an outsized impact on the future of our region. Bauer tells us: “If something’s going wrong, I always go right back to the center. I go back to the core and work my way out... That’s what should happen downtown.” Downtown Springfield is core to 417-land. It’s the past and the future. It tells our story, and surely that story is big, rich and enduring enough to offer roles for each of us.—Lucie Amberg